20 Jun, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Land taxation

- Is the disputes process fair?

- How much tax could legalising cannabis yield?

Transcript

Inland Revenue has just released an Interpretation Statement IS22/03 income tax – application of land sale rules to co-ownership changes and changes of trustees. Now, this is actually quite an important Interpretation Statement because it looks at whether the land sale rules in the Income Tax Act will apply when there is a change of co-ownership in an interest in land or a change of trustee.

It’s important because the Income Tax Act has provisions where a tax charge arises, where there is a disposal of land. And the question that’s been raised is whether any changes in ownership or changes in trustees represent a ‘disposal’ for the purposes of these rules, because obviously, if they do, then that could have significant implications under the bright-line test, for example.

The Interpretation Statement concludes when you consider the ordinary meaning and applied case law in context a disposal for the purpose of the land sale rules means or requires a complete alienation of the land by the disposal. In other words, that person must get rid of the land.

And helpfully the Interpretation Statement includes a number of transactions as examples. Where there’s a change in the form co-ownership, where the proportional shares or notional shares do not change, that is not a disposal for the purposes of this land sale rules. On the other hand, if there is a transfer between co-owners where neither’s interest is fully alienated, but the proportional share or notional share of a co-owner is reduced. there would be a disposal for the purpose of the land sale rules by that person to the extent that interest is reduced.

Inland Revenue’s argument in support of this is that because, although they’ve not fully alienated the whole interest in that land, they have fully alienated a part interest in that land. And similarly, if there’s a transfer that adds a new owner, there must be a disposal involved for the purposes of the land sale rules to the extent that the share or notional share of an original owner or co-owners in that land have been reduced. Similarly, a transfer that removes the co-owner would also be disposal by that departing co-owner of their interest in land.

Now on the matter of a change in trustees of a trust that will not be a disposal for the purpose of the land sales. And that’s because the Income Tax Act treats all trustees of a trust as essentially a single person. And therefore, in this case, disposal does not include a transfer to yourself, i.e. in the same capacity. Trustee swaps out, new trustee comes in, the title has to be reregistered and that’s not a disposal. On this basis, I think most people generally thought that was the case. But it’s good to see Inland Revenue come out and make that position clear.

There’s a useful table in the Interpretation Statement setting out examples of the Inland Revenue conclusions on this. There’s also a handy fact sheet available.

Heads the IRD wins, tails you lose (because you will never be able to afford to challenge their decisions)

Moving on, last week I referred to an Inland Revenue Technical Decision Summary. Now these technical decision summaries are issued by Inland Revenue’s Tax Counsel Office following an adjudication in a dispute or as part of the private rulings process. As I mentioned, they’re interesting to see because although they’re not binding on the Commissioner of Inland Revenue, they do give an indication of the types of cases Inland Revenue is encountering, and their likely thinking on an issue.

How taxpayers and Inland Revenue resolve matters where they cannot agree is an important part of any tax system. Inland Revenue has just released an exposure draft of a revised standard practice statement on the operation of the disputes process. When finalised, this practice statement is intended to replace two previous practice statements, one which dealt with where a dispute resolution process has been commenced by Inland Revenue, and the other where the dispute resolution process is started by the taxpayer.

Inland Revenue has decided to merge the two into a single statement and include some updates to the process, taking into account some relatively minor legislative changes that have happened recently. These relate to the introduction of what’s termed “reportable income” and “qualifying taxpayers” as part of the auto calculation of assessments process. The dispute process has been tweaked to deal with the introduction of these terms concept.

This is fairly routine maintenance by Inland Revenue. However, I think it ought to have taken the opportunity to look at the dispute process much more closely and whether it works for well as everyone involved with it as it should.

It so happens this is something I looked at for the Tax Working Group back in 2018. And in researching the matter I came to the conclusion that there are quite a few issues with the present dispute regime. In particular it’s expensive, very time consuming, and its costs act as a barrier to all taxpayers, but particularly smaller taxpayers.

Inland Revenue’s Adjudication Unit is part of the disputes process. It gets involved after there has been the initial stages of a Notice of Proposed Adjustment, or NOPA, and then the Notice of Response (NOR). After those formal positions have been issued by the parties to the dispute they then try and resolve the matter through negotiation. And if they can’t, it can be referred to the Adjudication Unit and.

Geoffrey Clews QC was involved in making some minor changes to the dispute process, to improve it about ten years ago. He commented on his experience working with Inland Revenue officials “reinforced the impression that [Inland Revenue] is very conscious that it presides over a tax administration which is weighted in its favour. It is reluctant to see that change.”

This is perhaps not surprising, but it should also be a bit of an alarm bell.

And then separately, two Supreme Court justices, Justices Glazebrook and Young, raised concerns about whether the dispute process was deterring taxpayers. They both noted there’d been a significant decline of tax cases coming through the court system. It’s now down to maybe 10 or 12 a year.

Justice Glazebrook, who is a former tax lawyer commented further on the disputes process in a speech to the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand Tax Conference in 2015.

“What is not so positive is the concern that the dispute resolution processes, even in simple cases, takes a lot of time, effort and therefore cost to complete. When this is coupled with the new penalty and interest regime, with its differential interest rates for taxpayers and the revenue, the concern is that taxpayers are ‘burnt off’ by the taxation disputes process. This means that taxpayers may be forced to settle legitimate tax disputes as they cannot afford the time or money necessary to continue court proceedings.”

Now, this draft statement of practice doesn’t address these issues. It’s not designed to because it’s intended to be just a largely restatement of the existing system. However, I think Inland Revenue should not be afraid to have a further look at think about how the dispute process currently works. It’s been ten years or more since we last looked at it. As I said things that’s notable is there isn’t a lot of activity going through the courts. Although everyone’s right now waiting to hear what the Supreme Court’s going to be saying about tax avoidance in the Frucor court judgement.

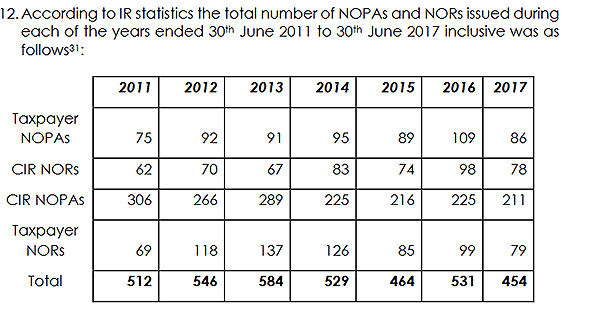

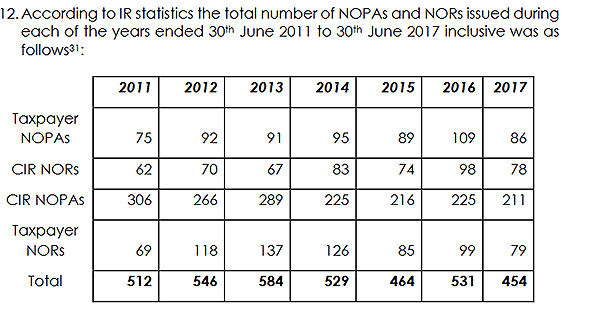

According to data supplied to me by Inland Revenue back in 2018, the average number per year of NOPAs and NORs i.e. matters in dispute over a seven-year period was 517. Now, in the context of nearly 5 million active taxpayers on a pretty controversial topic where people’s opinions and interpretations differ quite markedly, 517 disputes a year seems incredibly low.

The counterargument would be the process is working properly and the issues are being resolved much earlier. To be fair, that’s certainly true to an extent. But a cynic might also say Inland Revenue is not picking up enough of this stuff either. That may come down to a question of resourcing. Inland Revenue believes it’s fully resourced, properly resourced but looking from the outside I’m not quite so sure.

Although it’s always good to see Inland Revenue clarifying matters and updating its statements of practice, I think there is a major point still to be addressed about whether the disputes process is working as it should and if it’s not, what can we do to improve it?

Tax, cannabis, and gangs

And finally, this week, a quirky story coming out of Christchurch caught my eye. Brendan Crocker appeared in a district court this week charged with cultivating cannabis and for possessing a Class C drug for the purpose of selling In the course of his hearing it emerged that he admitted to starting a company so he could pay tax on his sales. That’s one of the more unusual excuses involving tax I’ve seen, too. Crocker claims he gave away about 80% of his cannabis candy in order to help people in pain and was only selling the rest to cover the cost of making it.

Gangs are currently in the news and there’s plenty of concern about the increase in gang violence in and around Auckland. Now it’s well known that one of the things that fuels gangs and gang tension is the trade in illegal drugs. This is where tax comes into play. Why not legalise or decriminalise cannabis? By doing so, we’d take control of the supply away from gangs, and hopefully therefore reducing their influence. Many countries have done this with Thailand one of the latest, and quite a few states in the United States have done it as well.

Once the sale of cannabis is decriminalised, it can become a useful source of tax revenue. And of course, that tax revenue can be used to deal with the problem of gangs and drugs. As I see it, it’s a win-win.

Colorado in the US. has a population of about 5.8 million, roughly comparable to ourselves. It legalised cannabis way back in 2014 and it publishes monthly records of its marijuana tax take. Currently it’s around US$19 million per month, which is roughly NZ$30 million, give or take, which equates to around about $350 to $360 million a year.

To put that in context, that tax revenue is probably more than what is going to come from the Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 international tax reforms that I discussed last week. Now they are a big deal for international tax, but the actual cash benefit for New Zealand is probably not as significant as many people might think.

On the other hand, cannabis, illegal drugs, gangs and the accompanying violence and threats is a problem as well as great cost to us. So that’s a proposal for someone serious to consider. Legalise cannabis, get some useful tax revenue. And then use that to help deal with the problem of drugs and gangs.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. ’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

13 Jun, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue backs away temporarily from controversial proposals targeting tax avoidance

- Tax and the first Emissions Reduction Plan

- Delays mount for the OECD’s ambitious tax plan

Transcript

The big news this week is the decision by Inland Revenue and the Government to pause implementation of two controversial proposals aimed at tackling potential tax avoidance around the 39% tax rate.

The first proposal was to treat sales of shares in the company, which had large amount of undistributed tax paid income as a dividend rather than a tax-free capital gain.

The second proposal was looking at the provision of personal services through interposed entities such as companies and trusts. Here Inland Revenue was proposing to broaden the range of situations where the income of the interposed entity would be deemed to be that of the individual actually providing the services. Now this proposal was criticised as going far too far and unfairly targeting tradespeople and independent contractors in particular.

Initially both proposals were to be part of legislation to be introduced in August and would have come into force from 1st April next year. But in the face of some robust criticism that the proposals went too far and concerns about unintended consequences they’ve been withdrawn for further consultation.

I think this is a wise move by the Government. Yes, the proposals were unpopular, but the Issues Paper seemed rushed and there were many concerns voiced by myself and many others that the scope of the paper went too far and there were bound to be unintended consequences.

My understanding is now we are likely to see a revamped issues paper for more consultation probably later this year. But notwithstanding the fact that there’s been a pause put on these proposals, taxpayers should still be careful around attempts to minimise tax, either through share sales to related parties such as a trust, (I had no issues with the Government’s dividend proposals in that regard), or to try and use a trust or another interposed entity to try and minimise income taxed at 33 or 39%.

An idea of some of the issues that are involved in this has come out in a recent Inland Revenue Technical Decision Summary. Inland Revenue has recently begun releasing technical decision summaries from its Adjudication Unit which gets involved when there are formal disputes between Inland Revenue and taxpayers. Although these technical decision summaries are not formally binding on Inland Revenue, they give people an indication of what might be Inland Revenue’s view on a matter.

And this particular adjudication decision summary involved income tax controlled foreign company issues and double tax agreement. It appears that at the heart of it was an attempt by a taxpayer to minimise the taxation of personal income through a pair of associated companies.

The taxpayer in question was a citizen of the United States and therefore is automatically deemed resident of the United States. As people may be aware US citizens have to file tax returns in the United States regardless of where they might actually reside. This particular person was employed as a CEO of a New Zealand company under an employment agreement. However, the taxpayer provided these CEO services through a US company (US Co) and another New Zealand company (NZ Co). The taxpayer was the sole director and shareholder of both US Co and NZ Co. There were various service agreements involved. Quite a bit going on here.

Inland Revenue investigated this arrangement and concluded that large withdrawals from a NZ Co bank account represented taxable income. It also saw similar withdrawals from US Co together with a series of deposits into US Co’s bank accounts. Inland Revenue considered the US Co expenditure to be private and non-deductible. It also considered the payments going to US Co as remuneration under a service agreement.

Inland Revenue ultimately held that US Co was a controlled foreign company and therefore the taxpayer had controlled foreign company income from that company. Furthermore, although the taxpayer as a US citizen had to file a US tax return, under the double tax agreement with the United States he was a New Zealand tax resident. This meant New Zealand had the sole right to tax the disputed payments.

The taxpayer lost every counterargument and for good measure, Inland Revenue slapped him with a gross carelessness shortfall penalty, which can be up to 40% of the tax involved in relation to the payments that were deemed to be remuneration and the attributed control foreign company income.

It’s quite an interesting case because we don’t often see decisions involving the double tax agreement in relation to the United States. It’s also interesting to see the sort of arrangements that Inland Revenue is keen to stamp out and will definitely be targeted in any revised proposals. I think it’s quite possible, although it’s not mentioned here, that the existing rules may have applied.

Anyway, this technical decision summary is a warning that Inland Revenue may have withdrawn some proposals, but it is still looking at these issues. You therefore need to have your ducks well lined up if you if it decides to investigate further.

Tax as a environmental change motivator

Moving on, the Government’s first Emissions Reduction Plan was released in the run up to last month’s Budget. The release was overshadowed by the Budget, but now we’re past the Budget it’s interesting to take a look at the document.

The Tax Working Group spent some time talking about environmental taxation. But in the midst of the focus on the capital gains issue its commentary on environmental taxation was largely ignored.

The Tax Working Group’s conclusion was “there is significant scope for the tax system to play a large greater role in sustaining and enhancing New Zealand’s natural capital”. Against that background it’s interesting to see what was in the Emissions Reduction Plan about the potential role of tax. And the answer would be at this stage, not much.

The full plan as published runs to 348 pages of the document. Tax is mentioned just four times, three of which are in passing. The only specific tax proposal is within Action 10.2.1 accelerating the uptake of low emissions vehicle which proposes investigating ‘how the tax system can support clean transport options to ensure low emissions target transport options are not disadvantaged.” And one of these areas would be the tax treatment of employers providing free public transport.

Given that the Tax Working Group put some emphasis on environmental taxation this is a surprisingly light approach. It is definitely worthwhile investigating what the tax system could do about not penalising clean transport options. But in my view, the Emissions Reduction Plan could have gone much further in and be more specific about particular tax actions.

For example, could we adopt the approach in Ireland and in the UK where fringe benefit tax on company vehicles is determined by the level of emissions? With regards to FBT it could be worth looking at how the work-related vehicle exemption is actually operating in practice and whether through people’s misunderstanding it’s accidentally led to the proliferation of high-emission twin-cab utes. Tightening the application of FBT around the provisions of car parks could be another option. There’s plenty to consider in this space.

Still on the environment, earlier this week the primary sector climate action partnership He Waka Eke Noa released its proposals for reducing emissions in the agricultural sector and how agricultural emissions should be priced.

It’s proposing a farm-level-split-gas levy, which requires each farm to calculate the long- and short-lived gas emissions. This will then determine a levy cost for that particular farm. This split gas approach will apply different levy rates to long- and short-lived gas emissions. And if there is on farm sequestration going on, that will then that will be recognised and would offset the cost of the emissions levy.

Wisely in my view the levy revenue is to be invested in research and development. There’s also going to be a dedicated fund for Māori landowners. My view around environmental taxation is whatever is raised should be reinvested to help drive down emissions rather than fund general government expenditure. Anyway, there’s some interesting stuff in these proposals. Listeners may recall I spoke to John Lohrentz a couple of years back about his proposal for a progressive tax on biogenic methane emissions. This seems to go somewhere along those lines.

The taxation of agricultural emission is highly controversial and there are already calls that what’s proposed doesn’t go far enough. I certainly think this is a topic which is not going to go away. The Tax Working Group was right to suggest tax could be used as a tool much more than it is currently. We should expect to see much more investment in this area and into exploring what the role of tax can be in helping reduce emissions.

BEPS reform stumbles in the US and EU

And finally, this week, a little bit more about the progress on the OECD’s ambitious international tax agreement. Tax fundamentally is politics, and it appears that politics is, as I expected would happen, starting to come into play and delay moving this forward.

Inevitably part of this involves the United States although interestingly it appears the problem in the United States is the necessary legislation is getting held up because it’s tied to spending proposals as part of the U.S. Government’s budget. The tax proposals do not appear to be the issue. What particularly catches my eye at this point is it appears the Republicans are not doing anything to move it forward, but they’re not actively doing too much to stop it at this stage. In other words, they seem to be prepared to help to allow these proposals to move through. You can imagine, though, that the likes of the companies affected, such as Google and Meta, the owner of Facebook, are certainly lobbying fiercely in the background.

Over in Europe the other political headache that’s emerged involves Poland. Initially, the big objection was likely to happen there with the European Union obtaining the unanimous approval of its members would have been Ireland pushing back at the proposed minimum corporate tax rate of 15% as it is above its current rate of 12.5%. However, Ireland appears to have come round on that matter. Instead, it appears that Poland have decided to throw up objections. But these appear to be the Poles basically looking to use their objections as leverage in a dispute with the EU over receiving pandemic aid money.

Hopefully these matters will be worked through, and the deal will proceed because it is important for international tax. It certainly won’t happen as quickly as next year as originally was hoped. I always thought that was ambitious, given the scale of these proposals and the requirement for 130 jurisdictions to get all the legislation lined up and ready to go by 2023.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. ’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

7 Jun, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- New details around the Cost of Living Payment, wealth taxes and windfall profits taxes

- Car travel reimbursement rates

- Longer-term perils of cheating on GST transactions

Transcript

Inland Revenue has now released more details about the requirements for receiving the Cost of Living Payment and how it will be administered.

Firstly, there is no need to apply for the payment. It will be made automated automatically if a person is eligible. The key thing is to make sure that Inland Revenue does have your correct bank account into which the payments can be made. Apparently, Inland Revenue only has records for just over 79% of potentially eligible people

As previously advised, they were going to be three payments, which will be made on the 1st of August, 1st of September, on the 3rd of October, the first working day of that month. Each payment will be made after a check of a person’s eligibility.

To summarise, a person is going to be eligible to receive this payment if:

- they earned $70,000 or less for the year ended 31 March 2022;

- are not eligible to receive the winter energy payment which means they are either receiving New Zealand super or a qualifying benefit;

- they’re aged 18 or over;

- are both a New Zealand tax resident and present here and are not in prison or deceased.

People receiving student allowances will get the payment if they meet the other eligibility requirements.

So the key thing, as previously advised, is to have had your income tax assessment made for the year to March 2022. So that means either Inland Revenue has auto-assessed it or you have filed an individual tax return which has been processed.

Eligibility is measured before each payment, so it’s quite possible that a person may not be eligible for one payment, but becomes eligible for a subsequent payment. For example, the person turns 18 after 1st of August, so will be eligible to receive the second and third payments. Alternatively, the person receives one payment but then starts receiving New Zealand Super, in which case they’re no longer eligible to receive the second and third payments.

The payment is not taxed and does not count as income for:

- child support

- Working for Families

- student loans

- benefits and payments from Work and Income.

Inland Revenue has also said it will not use the payment to pay off any debt a person may have with it, which is a welcome step.

Inland Revenue will keep checking eligibility until 31st of March 2023, although you will have until 31st March 2024 to provide bank account details to Inland Revenue. The Inland Revenue website has some useful examples of when persons are eligible and how they will administer it.

Travel claims by car

Briefly, Inland Revenue have also published the kilometer reimbursement rates for the 2021-2022 income year for business motor vehicle expenditure claims.

These rates may be used by businesses and self-employed to calculate the available tax deductions for the business use of a vehicle. They’re also often used by employers to reimburse employees for use of their own car for work purposes.

As you might expect rates have been increased but not significantly from previous years the tier one rate is now $0.83 per kilometer for the business portion of the first 14,000 kilometres traveled by the car including private use travel (an often-overlooked point).

Incidentally, the difference between the Tier 1 and Tier 2 rates is because the Tier 1 rate is a combination of the vehicle’s fixed and running costs and the Tier 2 rate is for running costs only.

Windfall profits taxes? Wealth taxes?

Talking about cost of living payments, over in the UK the government there has also announced some cost of living support measures. The interesting thing is that to pay for the £15 billion package it’s announced a 25% energy profits levy on the profits of oil and gas companies operating in the UK and on the UK continental shelf.

This windfall tax will apply to profits arising on or after 26th May this year. It’s a temporary levy which will be phased out when oil and gas prices return to “historically more normal levels” with the expectation that the tax will lapse after 31st December 2025.

The UK actually has a history of windfall taxes: that well-known tax cutter Margaret Thatcher imposed one on banks back in 1981 (I dare say a similar tax here would be popular) and in 1997 Tony Blair’s newly elected Labour government raised £5.2 billion on the increased values of previously privatised companies to fund a welfare-to-work scheme.

The idea of a windfall tax here in New Zealand has never been seriously discussed in recent years but it crossed my mind when the issue of the taxation of billionaires came up following the release of the NBR rich list earlier this week. There are now 14 billionaires in New Zealand with an estimated aggregate wealth of around $38 billion. Inevitably the question of how much tax they pay was raised. I repeated my longstanding view that some change to our tax mix to include greater taxation of capital is both necessary and inevitable.

Talking about it with The Panel on RNZ, Max Harris asked about a wealth tax. My favoured response is the Fair Economic Return Professor Susan St John and I have suggested. But there’s possibly an argument for a one-off wealth tax to capture the huge largely untaxed growth in property values over the past two years as a result of the Government’s initiatives around COVID.

If something like that happened, my belief is that any funds raised there should be used to speed up the transition to a low emissions economy, for example, by providing greater subsidies for lower emission vehicles and assisting communities to relocate from areas threatened by climate change. This is something I think we were going to see a lot more of, and particularly once (not if) insurers start withdrawing cover.

In the UK, a Wealth Tax Commission suggested in December 2020 that a one-off wealth tax was feasible. That proposal was for a one-off wealth tax payable on all individual wealth above £500,000, which at 1% a year for five years would raise £260 billion. The tax by the way, was to help restore the UK government’s finances in the wake of the COVID 19 pandemic. The proposal hasn’t gone anywhere at the moment, but it is an example of some of the current thinking we’re seeing around the topic of taxing wealth.

As I’ve said before the debate around taxing wealth will continue to run. In my view when you examine Treasury’s 2021 He Tirohanga Mokopuna statement on the long term fiscal position, tax increases of some sort seem inevitable.

The perils of tax short cuts

And finally, this week, another reminder about the perils of taking short cuts around tax. I got a call from a somewhat alarmed tax agent trying to unwind a GST scenario. This appears to have arisen because someone tried to avoid being GST registered in relation to a lease of land to a related party. At the same time that related party claimed GST in respect of a school building from which it runs a school. The issue has now boiled over because the school business is up for sale and it’s not clear who owns the building the school will operate out of, whether a proper lease is in place for those buildings and if so, what is the annual value of that lease? The result is that the potential sale of the business may not proceed.

I’ve seen similar impacts where a business hasn’t booked cash sales to evade GST & income tax, only to find that either when the business is up for sale, purchasers don’t have a true picture and the sale price disappoints. Alternatively, the owner applies for lending but because they have been suppressing their income, they haven’t got the necessary level of income. The lesson in all these cases is the same. Short term decisions to avoid tax consequences can often have longer term and much more adverse implications.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

30 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax, Uncategorized

- Will the IRD be able to deliver the cost-of-living payment?

- Potentially unwelcome GST surprise for farmers selling up.

- The latest developments from the OECD

Transcript

In the wake of the Budget, a Cost of Living Payments bill was introduced and has now been enacted. As part of the enactment a supplementary analysis report was released giving background to the proposed $350 payment. And this supplementary analysis has some very interesting commentary.

It appears the Cost of Living Payment was put together very much at the last minute as a response to the adverse effects of inflation on low to middle income households. According to these documents, this report was finalised on May 4th, barely two weeks before the Budget was delivered, which is very late in budget terms.

According to the document, Inland Revenue recommended against being the delivery agency for this Cost of Living Payment. The reason it gave was that it was concerned, that being asked to administer the payment would significantly impact its services to customers – taxpayers in plain English.

“The addition of this payment to their portfolio of services Inland Revenue already delivers will compromise Inland Revenue’s already stretched workforce and affect the taxpayer population, including the families and individuals that the payment would be intended to support them.”

Inland Revenue correctly identified that as soon as the announcement was made, they would get contacted about it which would put strains on their systems. It calculated a maximum of approximately 750 full time equivalent staff would be required to handle the payments to be made in the weeks of 1st August, 1st September and 1st October. Now, to put that in context, Inland Revenue staff as of 30th June 2021 was 4,200 full time equivalents. It would therefore need to use the equivalent of 18% of its staff to handle the delivery of this Cost of Living Payment. Quite clearly this would put strains on its system. The $816 million appropriation for the Cost of Living Payments includes $16 million to Inland Revenue for delivery of the services.

It’s therefore likely that Inland Revenue will need to hire additional staff, presumably contractors, on a short-term basis. And as we’ve discussed previously, the issue of contractors hit the courts with the Employment Court ruling that the contractors were not employed by Inland Revenue although I understand that decision is being appealed.

It also seems the Inland Revenue poured a bit of cold water on how the payments would be structured. According to the report, 55% of the total payments to be made will be to the middle 40% of households, 20% would be made to the bottom 30%, and 25% would go to the top 30%. There would be an estimated 478,000 households with children and 610,000 households without children who would receive a Cost of Living Payment. Although around 60% of all potentially eligible recipients will have annual income below $70,000, 10% would have family income of between $70 and $100,000 and 30% will have family incomes over $100,000.

And this led Inland Revenue to point out that potential equity concerns could arise because using individual income to calculate the eligibility for the payment rather than household income may result in different outcomes for households with the same income level. For example, a single person earning $100,000 won’t receive a payment, but a household with two people working who each have income of $50,000 would both receive the payments.

There’s also some analysis regarding how the eligibility is dependent on a person’s prior year’s income, which means the tax returns for the March 2022 must be filed. The paper notes that by the time Inland Revenue begins making payments on 1st August, it expects to have already raised individual tax assessments for approximately 3.2 million individuals, about 75% of individual taxpayers. But that leaves about 500,000 individuals, who may not initially receive the payment between the August to October payment run period because they haven’t filed their tax return. And this includes people who file through tax agents and have in theory until 31st March 2023 to file last year’s tax return.

This underlines a point I made in last week’s Budget commentary that you can probably expect tax agents to come under more pressure to get tax returns done on time so that those people who think they’re eligible may get a Cost of Living Payment. Overall, it’s some interesting insights into the administration of these systems and the Budget process.

GST pitfalls for the unwary

Now moving on, GST is probably the best example you can find of the broad-base low-rate approach to taxation policy. But even though it’s a highly comprehensive tax, that does not make it a simple tax. In fact, it’s full of pitfalls for the unwary. And I’ve been alerted to one which may affect farmers who are selling up.

Back in 2020, Inland Revenue caused some consternation when it issued Interpretation Statement IS20/05 on the supplies of residences and other real property. The Interpretation Statement reversed a long-established policy since 1996 on the sale of the farmhouse where the farmer might have used part of the property for their taxable activity, for example a home office in the homestead. Previously Inland Revenue’s position was that the sale of a farmhouse would generally be a supply of a private or exempt asset and not subject to GST.

However, in IS 20/05, Inland Revenue reversed that position and now said that the sale of the dwelling would have been useful for families who would now be subject to GST. The example the Interpretation Statement gave was if a GST registered farmer was claiming an automatic 20% deduction for farmhouse expenses, an Inland Revenue would expect that the property was therefore being used 20% of the time in the taxable activity and consequently sale of the farmhouse would be a supply in the course or furtherance of a taxable activity and therefore subject to GST.

This change has caused some consternation although some relief was given in the recently enacted Taxation Annual Rates for 2021-2022, GST, and Remedial Matters Act. This included a provision which allowed a deduction for the private use portion of a sale. Coming back to that 20% example I mentioned a moment ago, if 20% of the homestead was used for farming business and 80% for private purposes, there would be an adjustment for the output tax of 80% of the private portion. But that would still mean that 20% of the current value of the farmhouse at the time of sale would be subject to GST, which would be an increased tax burden for many farmers and undoubtedly a surprise for some.

Apparently Inland Revenue is now indicating that it may reconsider its position in its Interpretation Statement, which is a classic example of the military maxim “Order, counter-order, disorder”. But until that point is clarified, farmers who are selling their farm should be aware of this potential liability and seek advice on that transaction.

How the OECD influences our tax policy

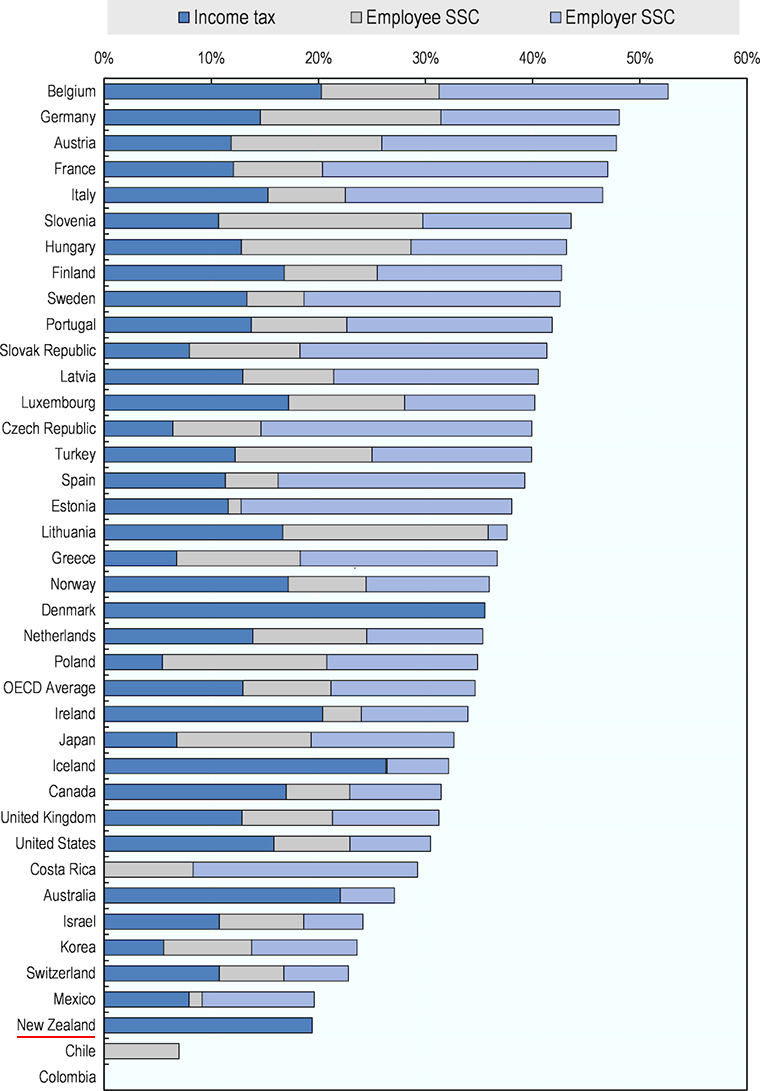

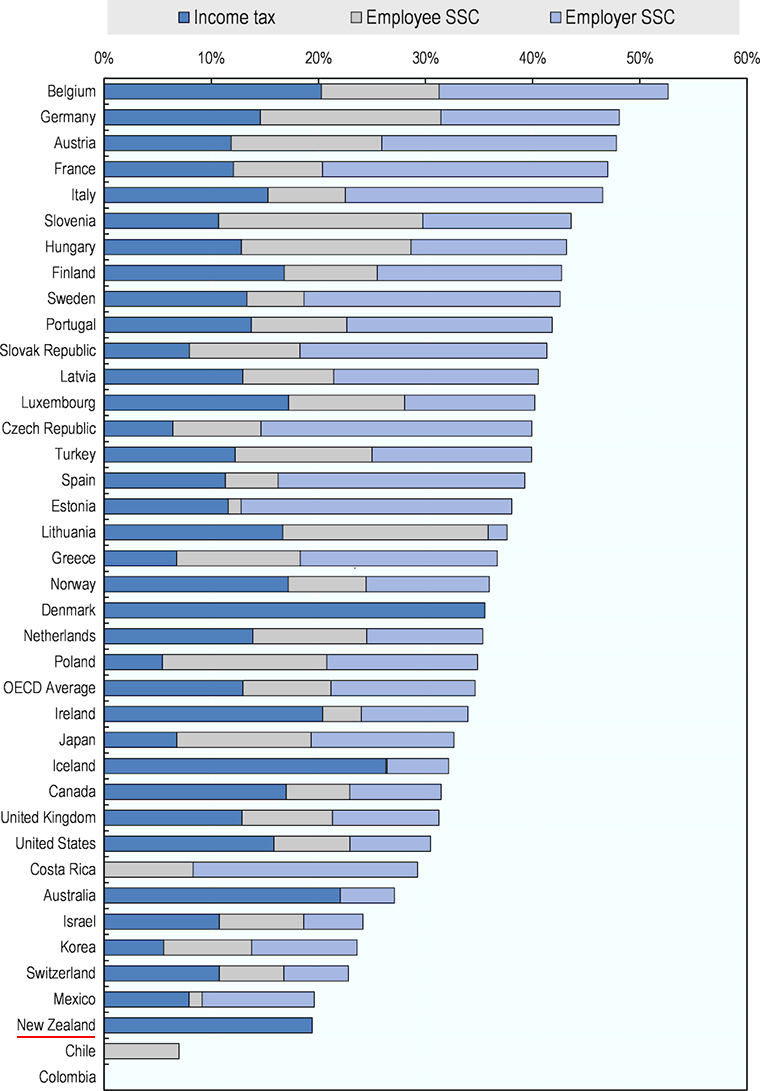

And finally this week, a couple of updates from the OECD. Firstly, it released its annual report on the taxation of wages. This includes its tax wedge analysis, which looks at the difference between labour costs to the employer and the corresponding net take home pay for the employee. Basically, the tax wedge is the sum of the personal tax income tax payable by the employee plus any employee and employer social security contributions plus any payroll taxes less any benefits received by an employee. (I think ACC is included for these purposes).

As can be seen New Zealand, scores very highly with a tax wedge of 19.4%, which is the third lowest in the OECD. The average in the OECD is 34.6%.

What this tax wedge measure also points to is the significance of Social Security and payroll taxes in other jurisdictions. One of the criticisms of the Government’s proposed social insurance scheme is it would be the first real Social Security tax that New Zealand has. It seems from early feedback this is one reason employers are pretty reluctant about the scheme. But even if the scheme was introduced, we’d still be down the lower end of the tax wedge.

Now the second OECD report was titled Tax Cooperation for the 21st Century. This was prepared by the OECD for the G7 finance ministers and central bank governors when they met recently in Germany. It’s particularly interesting because it picks up on what’s been happening with the adoption of the Two Pillar solution for international taxation we’ve talked about recently.

The OECD was asked to prepare was a report that would focus on the further strengthening of international tax co-operation and what recommendations it has in this field. This is looking beyond the implementation of the Two Pillar solution which makes it very significant, in my view, about the future administration of international tax.

For example, a key recommendation is tax administration should be seen as a common mission by tax authorities rather than a potentially adversarial exercise. The development of international cooperation is one of the biggest themes in international taxation in the 21st Century and is also probably one of the least understood. And I will repeat what I’ve said beforehand, most people are oblivious to the amount of information that is being shared by tax authorities at all levels. China, incidentally, has just signed up to the mutual agreement and protocols on that. So every major jurisdiction in the world is cooperating or looking to cooperate on international tax at some level. This is why this paper is important because it starts to map out and where that international co-operation might be going.

The report focuses initially on corporate tax saying there needs to be a reliable framework for cross-border investment. As just noted, tax administration should be seen as a common mission. There should be a collaborative approach with early and binding resolution.

The impact of going digital is emphasised and that it needs to speed up to improve engagement with taxpayers. There are also recommendations beyond corporate tax about moving to real time data availability for taxpayers and tax administrations to make efficient use of evolving technologies while maintaining data privacy and confidentiality.

The issue of data privacy and confidentiality is a developing area where taxpayers are starting to push back against tax authorities because they are concerned, rightly, whether everything is secure as it should be. Furthermore, some are, understandably, not too happy about information sharing.

Finally there’s a recommendation that advanced economies should commit to supporting developing economies so that they can fully benefit from the policy changes. This means building capacity which is going to be needed, especially for the implementation of the Two Pillar solution. Overall, this is a relatively brief but fascinating paper with potentially significant implications.

And just incidentally, on the international Two Pillar solution, the Secretary General of the OECD has now indicated that he expects that implementation will be delayed by a year until 2024. That doesn’t surprise me, given the scale of the project, because there’s a lot of legislation that needs to be put in place by the middle of next year at the latest. Inland Revenue have only just started consultation on the matter.

Still, the Two Pillar project has moved on quicker than some cynics might have expected. But as I’ve said previously, politics is likely to get in the way, particularly the upcoming US Congressional midterm elections. Anyway, as always, we shall bring you the news as it develops.

Well, that’s all for this week I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

23 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

So, much as expected, no headline tax surprises again. We will have to wait until next year for any changes to tax thresholds Interestingly, the matter of increasing thresholds was not raised with the Finance Minister during the Budget Lockup, although he addressed that in part by arguing the cost of living payment was better targeted than a general across the board threshold adjustment.

Transcript

The ongoing (but not quantified) effect of fiscal drag means tax revenue for the year ending 30th June 2022 is expected to cross the $100 billion mark for the first time to a total of $103.8 billion. The main growth is from PAYE, forecast to rise by $3.7 billion to just under $42 billion and corporate income tax projected at $16.7 billion up nearly $2 billion. (That includes an estimated $322 million from the New Zealand Superannuation Fund, down an eye-watering $1.8 billion from 2021 – illustrating the impact of the recent turbulence in financial markets, thanks Vladimir). GST receipts are also up over $1.2 billion from June 2021 to an expected $25.7 billion.

The big announcement was the cost of living payment of $350 in three monthly instalments starting 1 August (about $27 per week). The payment will be available to individuals who earned less than $70,000 per annum in the past tax year, and not eligible to receive the Winter Energy Payment – approximately 2.1 million New Zealanders. It will cost an estimated $814 million.

Eligibility for this payment will be determined by a person’s income for the March 2022 year. Most of those eligible will have their income determined by Inland Revenue’s auto-assessment process which is now underway. The payment is therefore an incentive for eligible taxpayers who have to file a tax return to do so as soon as possible. Not entirely sure my tax agent colleagues will welcome that development.

The temporary reductions in Fuel Excise Duty and Road User Charges will be extended for a further two months at an estimated cost of $235 million. Half-price public transport is also extended for a further two months and will be make permanent for 1 million Community Services Cardholders which seems a good initative. Extending half-price public transport should be a measure which helps in reducing emissions.

Small businesses are an important part of the economy, so the proposed Business Growth Fund is an interesting move. The Crown will initially invest $100 million alongside private banks. Through the Fund the Crown will take a minority interest in SMEs where equity finance would be more appropriate than debt finance.

The intention is for the BGF to be an active investor providing growth capital, but it would not take a majority position although it would have a seat on the board. It’s an interesting development based on similar initiatives in the UK, Ireland, Canada and Australia so we will watch with interest. Personally, I think a permanent iteration of the Small Business Cashflow Scheme would be a good long term initiative.

There’s a small but welcome change to Child Support rules with the scrapping of the rule under which the Crown retains the Child Support payments of beneficiary sole parents. From 1 July 2023 those Child Support payments will be treated as income.

Although there were no specific funding initiatives for Inland Revenue it’s interesting to dig into the formal Vote Revenue Appropriation. The total 2022/23 appropriation for “Services for Customers” is $721.8 million, an increase of $120 million or near 20% from the 2021/22 appropriation of $600 million. This increase is mainly due to re-categorisations and transfers including a transfer of $55.8 million for ongoing operating costs arising from the Business Transformation programme.

Breaking it down there’s an extra $9.4 million for investigations and over $37 million for tax return processing, both of which reverse falls in funding in the 2021/22 appropriations. The biggest increase though is for Services to Ministers and to inform the public about entitlements and meeting obligations which is up $56 million or 21,7% from 2021/22. I expect some of this will be to remind people of their eligibility for the cost of living payment, but there may also be initiatives about tax obligations and the cash economy.

In summary, a very boring Budget from a tax perspective although leaving income tax thresholds unchanged for another year is now something of a political hot potato for the Government. The intention appears to be to address this in next year’s Budget which is of course an election year. We shall wait and see.